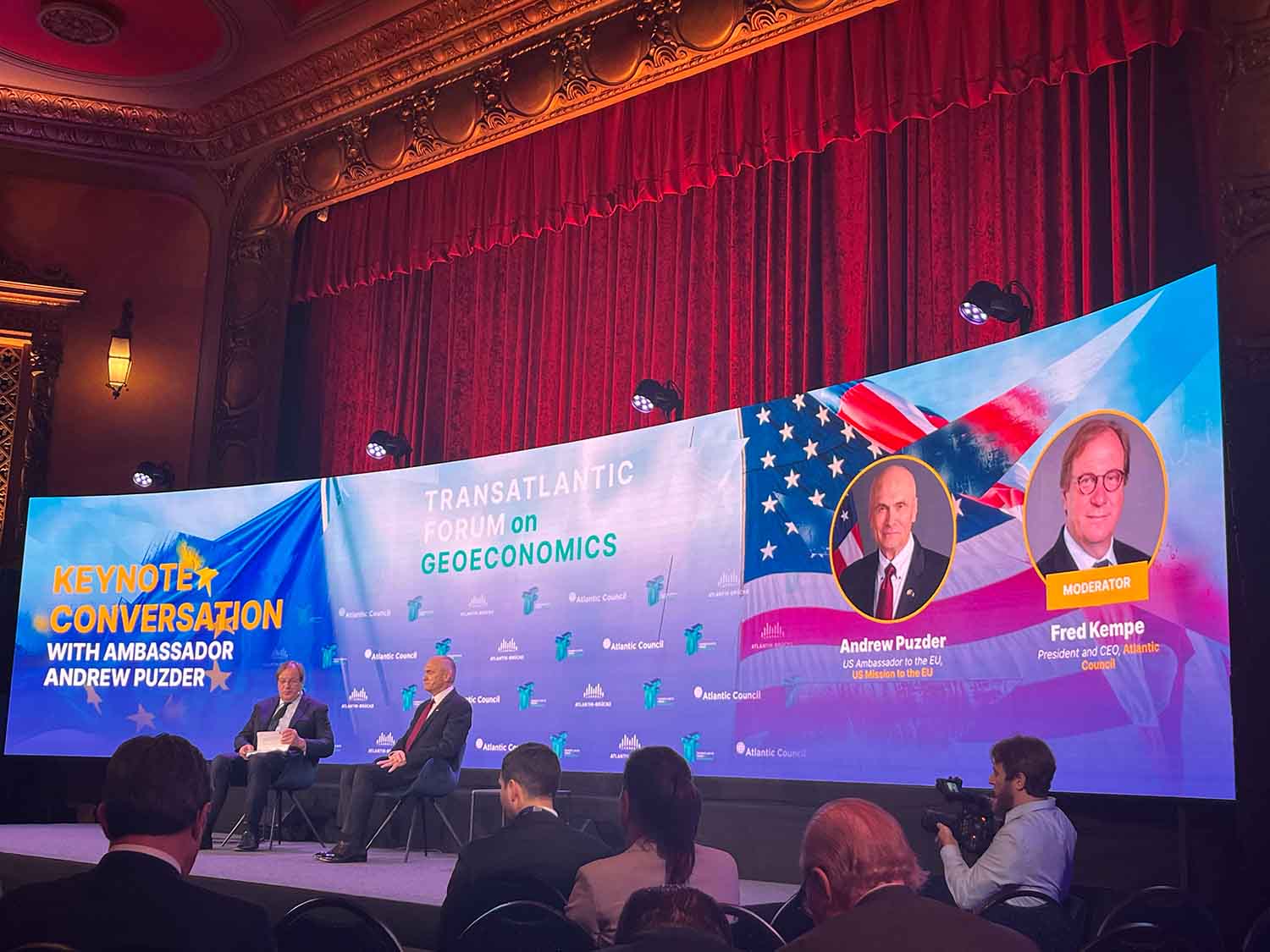

Reporting from the Atlantic Council Forum on Geoeconomics in Brussels

The chandeliers glittered in the ballroom of the Atlantic Council as diplomats, ministers, and executives filtered in for the opening session of the Geoeconomics Forum. The event promised high-level conversation on trade, technology, and global markets, but there was little illusion about the stakes: the EU–US relationship is being reshaped in real time by war, energy shocks, and the race for technological supremacy.

The panels that followed made one point clear: the old order has collapsed. What comes next will decide not only the future of Europe, but the structure of the global economy.

Author: Szilárd Szélpál

The War That Changed Everything

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine cast its shadow over the entire event. The conflict, now well into its third year, has inflicted staggering costs: close to a million lives lost, and nearly 20% of Ukrainian territory under occupation. Yet the war’s impact stretches far beyond the battlefield.

“Europe’s old model is gone — cheap Russian energy, US defense guarantees, Chinese supply chains. None of those are reliable anymore,” one panelist remarked. The line echoed through the room, summing up the strategic anxiety that permeated the forum.

For Hungary, which relies on Russia for 95% of its gas, the dilemma is especially acute. But the point was broader: Europe’s dependence on pipelines and imported fuels has become a liability. Without massive investment in new infrastructure and diversification of supply, the continent remains exposed.

The United States has poured billions into Ukraine’s defense. Washington, however, is growing blunt in its message to allies: Europe must do more. “Allies share burdens — that’s what makes us allies,” said one speaker, capturing the American mood.

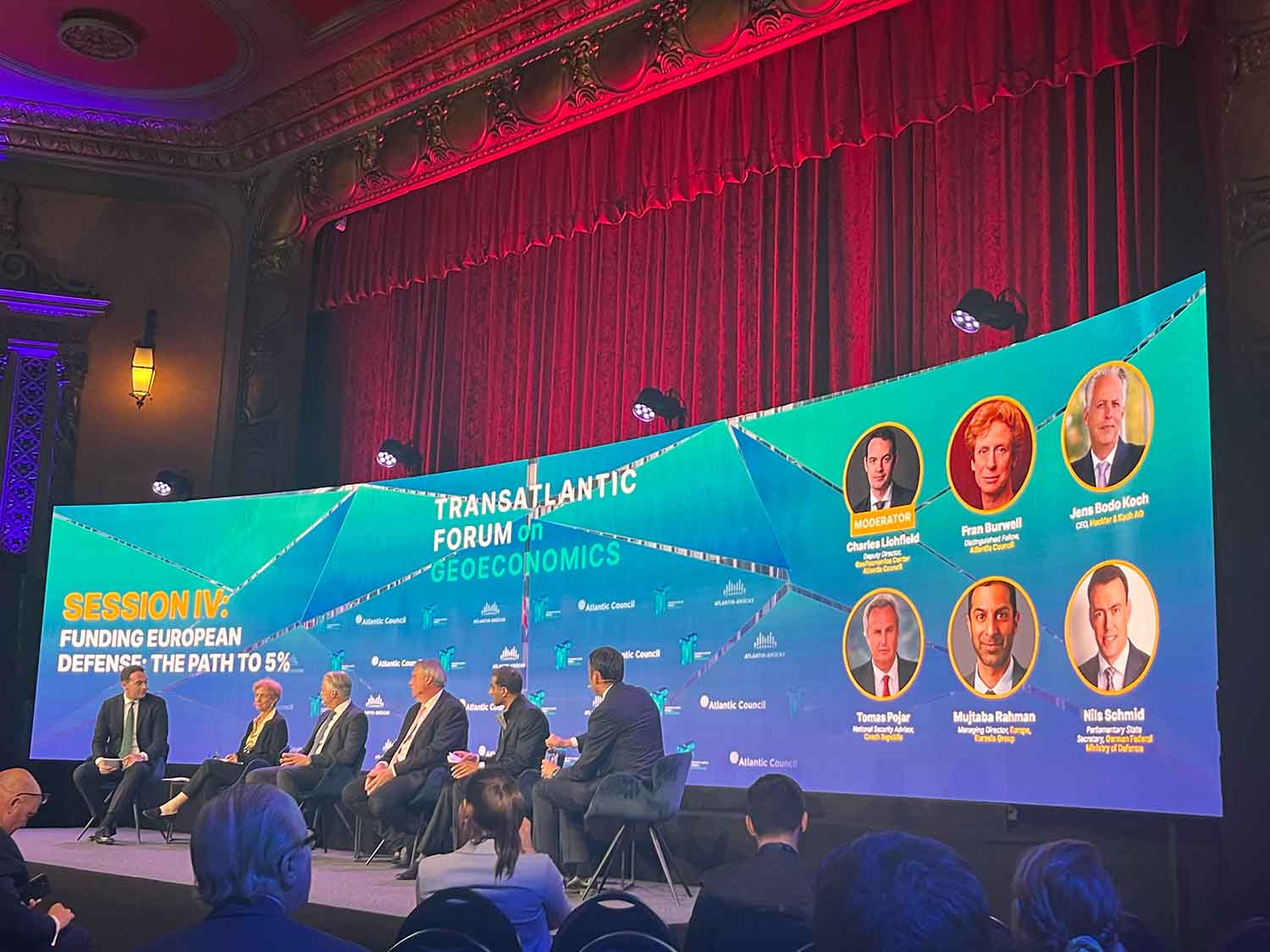

That logic extends to defense spending. NATO’s 5% of GDP benchmark for 2029 no longer looks unrealistic, several participants argued. The bigger challenge is building Europe’s own defense supply chain. As one strategist noted: “You can buy ammunition abroad. But if you want real security, you have to produce it yourself.”

€5 Billion a Day

The economic ties between the EU and US remain enormous. Every day, around €5 billion worth of goods cross the Atlantic. Yet behind the impressive numbers, tensions are rising.

From Washington’s perspective, too many trade agreements tilt toward Europe. In Brussels, the complaint is different: that US tariffs and political volatility inject damaging uncertainty into the relationship.

Steel and semiconductors became emblematic case studies. Europe has lost 17 million tonnes of steel production capacity in the past decade. Meanwhile, the US imports 40 million tonnes annually — most of it high-grade, processed alloy steel. In semiconductors, a unique interdependence has developed: the US designs and produces the most advanced chips, while Europe builds the machines required to manufacture them.

“This is a natural partnership,” one EU official insisted. “But one we must defend against protectionism on both sides.”

Complications abound. How should a car built in Germany, but containing Chinese steel components, be treated under US tariff rules? Should the whole vehicle be taxed, or only the Chinese inputs? “It sounds technical,” one trade lawyer noted, “but these are the questions that can paralyse supply chains.”

Green Steel and Carbon Goals

The debate over steel led to a striking conclusion: the green transition is less about electric cars than it is about industrial inputs.

“Green steel is the easiest way to reach decarbonisation goals,” one panelist said. “Not by tinkering with consumer products, but by transforming how we produce the building blocks of industry.”

Yet if Europe loses its industrial base — whether steel, cars, or chemicals — decarbonisation could backfire. Factories will simply move to China, and Europe will import high-emissions steel instead. Hence the push for “reindustrialisation”: restoring production capacity to European soil.

WTO Reform and the Global Trade Map

Another recurring theme was the fragility of the global trade system. The World Trade Organization, once the anchor of multilateral commerce, is increasingly paralysed.

“We need to reform the WTO,” a Commission representative argued. “To deal with overproduction, to resolve legal disputes, and to prevent the rules-based system from collapsing.”

Meanwhile, Europe is diversifying its trade partners. Today, 20% of EU trade is with US markets, but the other 80% is expanding: Latin America, Southeast Asia, the Pacific. To date, Brussels has signed 44 trade agreements with roughly 70 countries. The message was clear: Europe cannot afford to depend too heavily on either Washington or Beijing.

“The US builds, China reacts, Europe regulates”

Technology emerged as the most forward-looking — and perhaps most sobering — topic. Artificial intelligence is not merely a tool of efficiency; it is now understood as a national security issue.

Here Europe faces a daunting gap. AI adoption stands at 83% among American firms, 65% in China, and just 35% in Europe. “It’s not AI that costs jobs,” one speaker warned. “It’s the companies that know how to use it better than you.”

The structural disadvantages are clear: less venture capital, fewer engineers, and a regulatory environment that often stifles innovation. As one American participant quipped, drawing laughter and grim nods: “The US builds, China reacts, Europe regulates.”

AI also demands massive amounts of energy. Data centers and machine learning models consume vast power. “You can’t talk about AI without talking about electricity,” said a panellist. “This isn’t just a climate debate. It’s a question of national survival.”

The Energy Cost Divide

That point led back to energy policy. Access to affordable fuel is the dividing line between countries whose economies thrive and those that stagnate. Energy-rich states are attracting investment, while Europe faces soaring prices and industrial decline.

Companies deciding where to build the next generation of AI servers, semiconductor fabs, or battery plants will go where energy is cheap and reliable. Europe’s constrained energy supply risks pushing those investments elsewhere.

“The irony,” one speaker noted, “is that Europe regulates innovation, while also making the energy to power it less available.”

Toward Reindustrialisation

Despite the bleak diagnoses, there were hopeful notes. Maroš Šefčovič, Vice-President of the European Commission, made a compelling case for “reindustrialisation.”

“Every day, €5 billion worth of goods cross the Atlantic. That is opportunity. That is strength. But if we do not rebuild industrial capacity, we will lose both,” he said.

He pointed to daily commerce as proof of interdependence: “The US and EU are each other’s largest investors. We are not rivals. We are partners — but only if we understand one another’s goals.”

The implication was clear: reindustrialisation is not just about economics. It is about resilience, security, and restoring the foundations of prosperity.

A Relationship in Transition

By the forum’s close, the mood was one of wary optimism. The EU–US alliance is not collapsing, but it is changing. The familiar certainties — Russian gas, American security, Chinese labour — have evaporated. What replaces them remains uncertain.

As one participant summed it up: “This alliance isn’t just about defending Europe. It’s about shaping the future of the global economy.”

For more insights on Central European political risk, EU institutional developments, and transatlantic relations, follow CEA Magazine and the CEA Talk podcast.

Support independent analysis and journalism at CEA Magazine: https://centraleuropeanaffairs.com/donation

Cover photo credit: Szilárd Szélpál

Szilárd Szélpál served as an environmental expert in the European Parliament from 2014, where he utilized his expertise to influence policy-making and promote sustainable practices across Europe. In addition to his environmental work, Szilárd has a deep understanding of foreign affairs, offering strategic advice and contributing to the development of policy initiatives in this field.